How to Transfer Files Between Computers Using HDMI (Part 1: Plan)

Posted on: 2023-05-12

In this series of blog posts, I will discuss transferring files using an HDMI port to a USB port of another computer. The goal of transferring a file using HDMI is to share a file without using the computer USB or Internet, or Ethernet between two machines.

The blog posts are written as the solution is developed, and only the last post of the series contains the working solution. The goal of showing the intermediate step from the idea to the final solution is to teach different assumptions and failures along the journey.

Context

You may work on a computer with many security restrictions in some situations. For example, the Internet might be monitored or with an extensive list of blocked websites. USB might be blocked for writes and limited for reads. In addition, some security software is installed to restrict what can be installed on the computer or that the computer must be on a VPN, making transferring files outside this computer more straightforward. Regardless of the motive of all the security around the source computer, let's explore how to transfer files with all these restrictions.

Thinking Outside the Box

When I grew up, at some point, I realized that the lock on the door of a house was not so secure. Someone can through something on the window next to the door and come in. Indeed, it makes a mess and is easy to detect. Likewise, someone else can pick the lock and enter. There is a natural feeling that lockpicking a door or forcing an entry is hard, but when you put some effort into it, you realize that many security devices can get around by looking at other angles than the main one. Hence, instead of attacking the main door, let's tackle a communication vector: HDMI.

A secured computer does have many inputs and outputs, like a door or windows in a house. We must observe the unusual outputs to transfer a file outside the computer. USB, SD card reader, Internet, etc., are apparent and well secured. Similar to looking at a house and focusing on the main doors. However, one output is more open. Outside TV's shows where cartoon characters use a chimney to get inside the house, it is rarely used in real life to get inside. Thus, the home's security system never focuses on that entry vector. In our case, the chimney is the HDMI port. It is assumed to display data from a computer to monitor. This last sentence can be rewritten to: the HDMI port is assumed to transfer data outside the computer, exactly what we want!

The idea is to take a group of files and zip them into a single file. Convert the file into a video. Play the video to an HDMI that we control. Read the video from the HDMI into another computer with full access. Extract the zip file from the video and unzip.

Minor detail, installing software in the secured computer is not a walk in the park. A secured computer usually only lets you have administrator access and blocks most possibilities to install without IT. However, here comes the second part where we can exploit a vulnerability: greed. Many secured places love free work or free code and allow to a large degree, access to free libraries for their developer. Sometimes you can be lucky and have access to Brew, and you may have access to Github, but surely you have access to NPM or Cargo, which are library repositories of code. Thus, we can hide the code that will encode the file to a video in Cargo since we will develop the solution using Rust.

The Plan

The plan is to write a Rust library to encode the files into a video file. Of course, it could be done in another language, but Rust is what I am learning and that I know is accessible from many secured environments. Thus, using Cargo, we can access the developed Rust application on the secured computer without being suspicious. Also, there is always the possibility to hide the application code under another package that depends on our desired package. NPM/Cargo and open source libraries are known to be a nest of so many dependencies that it is easy to hide something.

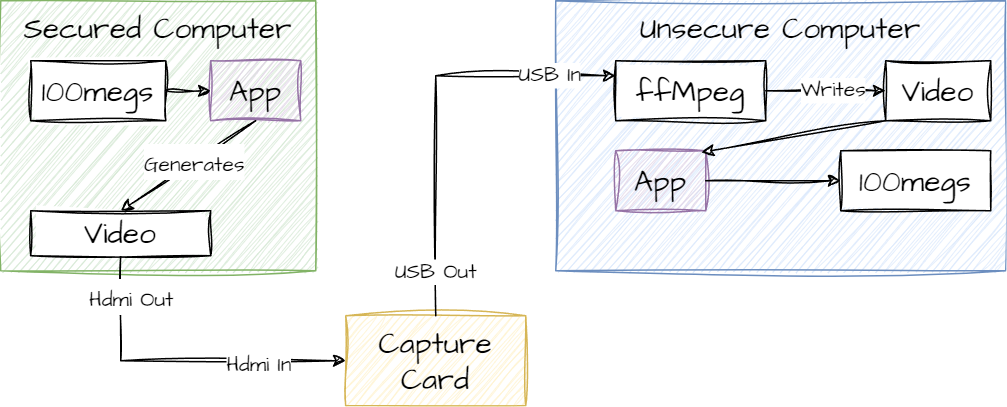

The next part is to play the whole video in fullscreen into an external display. Using HDMI from the secured computer to a cheap capture card. The capture card has an HDMI input and a USB output. From the perspective of the secured computer, it is a monitor -- nothing more. Thus, the plan is to have the Rust application (of ffmpeg) read the videos streaming from the capture card and save the video.

Finally, the Rust application on the unsecured computer will find the starting and ending point of the persisted video and extract the file.

Napkin Calculation

Before investing many hours, let's calculate how possible this plan is.

A cheap 30$ capture card provides few resolutions, like a monitor does. The one I have in hand says:

4k @ 30fps 1080p @ 60fps

Let's start with the HD (1080p). It means that we have a resolution in pixels of 1920x1080. The total pixel is 2.1 million pixels. At 60 fps (frame per second) it gives us 120 million pixel/second.

The same logic for the 4k: 2160x3840 produces 8.3 million pixels at a lower fps of 30. Still, the total is 249 million pixels per second.

I am not sure at the moment that I am writing this blog post that the secured computer can connect at 4k, nor that each pixel is unaltered during transmission (meaning the pixel color is the same from input to output). For now, let's assume there is no compression or alteration. If the hypothesis is wrong, we can use more pixels to correct the potential inaccuracy at the cost of transferring less information per second.

With the hypothesis that we can transfer 249 million pixels every second and that 1 pixel has three values (R, G, B) that has 8 bytes each, so we have 24 bytes, transfer into 249x24=5 976 million bits per second.

If we set a target of transferring a file of 100 megs (100 million bytes or 800 million bits), we could move the 100 meg files in less than a second.

Caveats

So far, the napkin calculation sounds promising. However, more is needed to encode the file into a video. Also, the most challenging part is the reliability of playing and capturing the video. The video is moving frame every second. There is a need to have the capture card and the reading computer to start the process with some seconds or milliseconds of difference. A synchronization mechanism will be needed to play the video on one end and consume it on the other. Also, I wonder if the video from the file on the secured computer will be without compression. It may also be possible to use the card at 4k.

Pacing our Expectations

To have a more realistic view, let's get our numbers into a more natural range and see if it is still worth it. Let's assume we can only achieve HD at 30 fps. 2.1 million x 30 fps gives 63 million pixels per second or 1 512 million bits (RGB = 3 bytes = 24 bits). It would still be under a second for 1 file of 100 megs.

If we tune down even more by assuming that pixels next to each other blend because of compression, then we need to have a more precise way than relying on the exact RGB value. In the video, a slight change of an R or G or B does not affect our perception of the content. However, a single bit shift can corrupt a file. We could use black/white pixels for each bit of information. That might bypass some artifact issues in this chain of video encoding/decoding but at the cost of efficiency. If each bit of the file is black or white, depending on the bit value, we need 800 million pixels for 800 million bits (100 meg files). But, as we calculated in this section, we are still in the worst-case scenario of transferring 1 512 million bits per second.

I am OK with waiting a few seconds to ensure a 100% success rate. That way, we could have more than 1 pixel per bit, making the square in the video bigger. With more prominent "spots," it gets harder to read back incorrect values. If instead of having 1 pixel (black or white) we would double the pixel to have 4x4 pixels, we would be four times less efficient in terms of size but still able to transfer 300 million bits of information per second, which would require us to a little bit under 3 seconds for 100 megs. Reasonable.

Alternative Ideas

In code theory, there is something called fountain codes that is a erasure codes allowing partially altered content to be recovered. It adds size to the payload, but because the information is duplicated and spread toward the stream of information, it can be recovered. The concept is called error correction code. A performant algorithm is Raptor Code. It might be a potential approach since, from what I am reading, the overhead is only 2% for a probability of 99.9999% of recovery (source).

Next Steps

The next step is to explore how to encode file content into a video with a small prototype. The prototype must be flexible enough to modify the fps, resolution, and criteria for generating the pixel into these frames.