My experience migrating TypeScript libraries to Rust

Posted on: 2023-02-16

I recently migrated a couple of Rust libraries from TypeScript using a subset of features of well-known TypeScript libraries. So far, I have the following Rust repositories:

- Stegagnography: Hide message into an image

- Hilbert Curve: Perform hilbert calculation

- Pretty Bytes: Format the number of byte in a human readable format

- Pretty Duration: Format a time in a human readable format

I am still a novice with the Rust language and ecosystem but I enjoy learning by practicing. Here are a few takeaways from these fours projects

Configuration Files

Instead of using a package.json you have a cargo.toml. Very similar, with one difference: you do not have all the scripts that you use. Only the metadata of your application (name, version, author, etc.) and dependencies on other packages.

I'm using the readme.md to document the commands that I often use like generating a build, test, coverage, etc.

Outside the cargo.toml, a small file name rust-toolchain.tom specifies which version of Rust you are using. All my projects have:

[toolchain]

channel = "stable"

I also have a bash file in all my projects for code coverage. It performs the test with some environment variables and cleans up the generated files from grcov. The bash file:

CARGO_INCREMENTAL=0 RUSTFLAGS='-Cinstrument-coverage' LLVM_PROFILE_FILE='coverage-%p-%m.profraw' cargo test

grcov . -s . --binary-path ./target/debug/ -t html --branch --ignore-not-existing --excl-line "///" -o ./target/debug/coverage/

rm coverage*.profraw

rm default*.profraw

At first, I was confused about how to install a library since I rely on npm install <lib here>. In Rust, you can use a command, but writing in the cargo.toml is enough. Then, VsCode will know that the file has changed and get the Intellisence. And the library downloads during the build step.

Main and Lib

One exciting aspect of Rust is that you have a terminal entry point and a library entry point in your project. Hence, when you deploy your application, it is available from a terminal and any other Rust project. It is not required, but I found it very useful. I always have my main.rs referencing my lib.rs.

It means that anyone can download your terminal application by installing your code (which will download the code, build and install it into your $path);

For example:

cargo install ripgrep

rg --help

Mod, Pub Mod, and Use

A confusing aspect is the use of mod. There is a new and deprecated way to manage files and modules with Rust. In short, you should no longer rely on a file named mod.rs anymore.

Mod

Instead, you create a file with the exact same name as the folder with all your Rust (.rs) files.

src

├── lib.rs

├── main.rs

├── utils

│ ├── binary.rs

│ ├── encryption.rs

│ ├── function.rs

│ └── options.rs

└── utils.rs

A simple way to understand mod is to see the instruction has a way of declaring that you will be accessing a specific module.

Pub Mod

In that example, the utils.rs defines the module (mod utils), which module is available for the lib.rs and main.rs by making it public (pub mod) outside the folder with pub. Coming from TypeScript/JavaScript is similar to having an index.ts that exports a collection of functions, classes, and interfaces.

For example, in the utils.rs:

pub mod function;

pub mod options;

pub mod binary;

pub mod encryption;

Inside your lib.rs you must call mod utils and then optionally use use to create shortcuts.

// Access

mod utils;

// Imports

use crate::utils::function::{add_message_to_image, get_message_from_image};

use crate::utils::options::SteganographyOption;

A way to visualize the pub mod is to see if the instruction has it copies all the content of the module inside the invoked. In that case, we would copy all the public traits, functions, etc., of the module function, options, binary and encryption into the util mod. Instead, we could erase these four files and have all the code directly into the utils.rs but that would not be an organized code.

Use

So, use is always optional. In that case, because we are defining two functions and one trait, we can now directly call:

add_message_to_image(.....)

// or

get_message_from_image(....)

// or

SteganographyOption

Without the use we would need to :

crate::utils::function::add_message_to_image(.....)

// or

crate::utils::function::get_message_from_image(....)

// or

crate::utils::options::SteganographyOption

A simple way to understand use is to create an alias to avoid repetitive typing words.

Tests

Testing has some benefits and inconveniences. First, you do not need to struggle to configure anything. It is available right away. Rust patterns of having unit tests directly in the file are interesting, but also you can have project test and even test in your comments. Code in comment opens the door to an inconvenience: the tooling needs to be more suboptimal for unit tests with comments. No color or auto-complete.

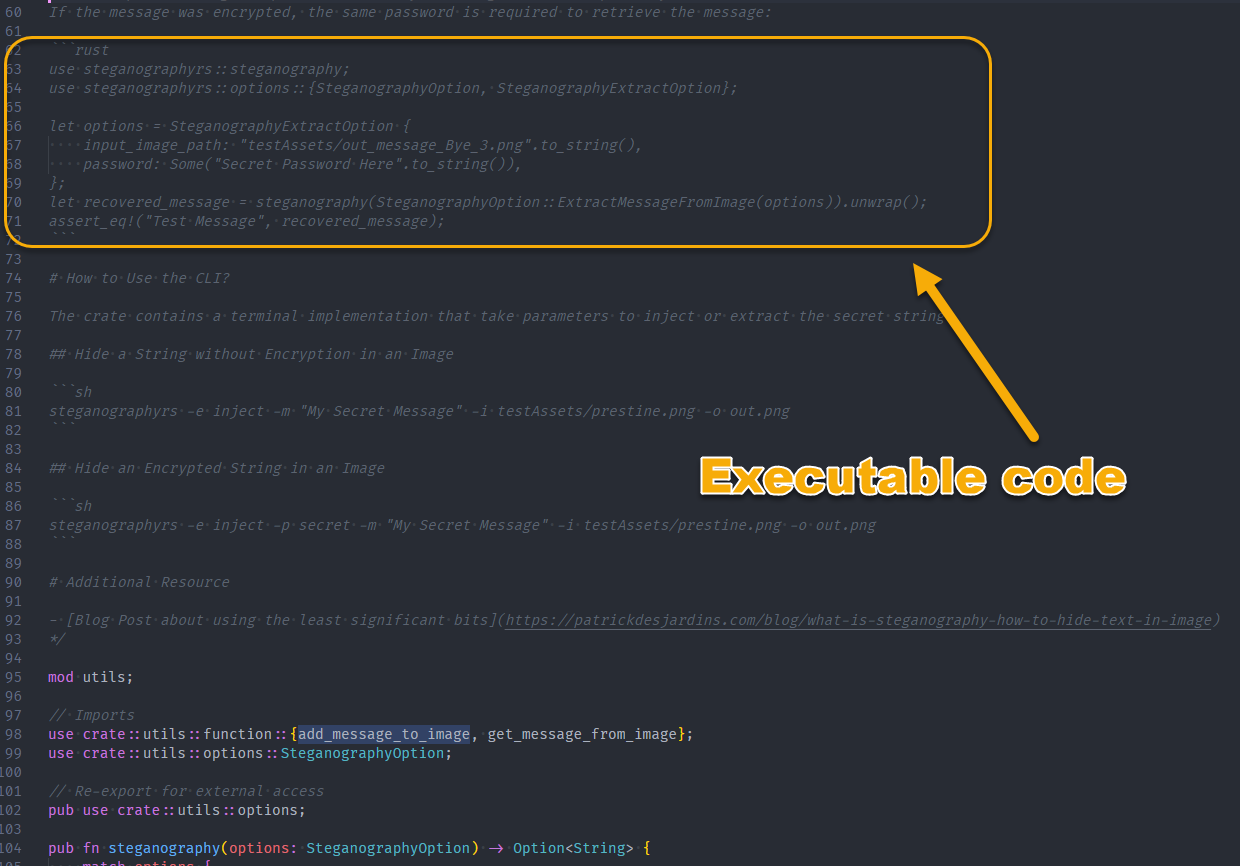

Here is an example of code that is executed if you execute cargo test

Debugging works until it does not. So far with Visual Studio Code, testing worked well, but I had few evenings where it stopped working without much explanation. Is the issue VsCode, Rust, lldb or because I'm working in wsl? Too many layers of potential failure. However, debugging a NodeJS in TypeScript can be painful. I have a project with half a dozen launch configurations depending on the year it was working with a specific testing framework. Rust relies on lldb, so you need to install something besides Rust. It would be great if it were slightly more in-the-box. However, no mapping issue or breakpoint that cannot be hit once everything is working.

Running unit tests is slow in Rust. Also, I have not found a native way to run failing tests (watch mode), making the process even slower. Code coverage code is more integrated as well.

On the negative side, my tests are more organized in TypeScript or other languages because, in Rust, you cannot nest your test, leaving them flat per file. For example, in TypeScript (with Jest) you can have many levels of describe, which help with organizing per categorie.

Mocking a structure is impossible if you want to mock only a portion. Moreover, coming from other languages, it does not seem intuitiv.

Documentation

Using Cargo third-party is a fantastic experience. With all third-party libraries, you can from VsCode see the source code and the documentation.

Also, a tool generates for each package's documentation, which encourages having good ones.

Using cargo doc generates a website for all your public code. cargo doc --open --document-private-items with all private items. A significant mechanism is that when you push into the cargo package website, it automatically generates the website for your help.

Crates.io: Package Management

Similar to NPM in the JavaScript ecosystem. You can see the one generated for the Steganography. It also automatically generated a website on docs.rs from the source code.

The package management is well integrated, and so far, I have no concerns.

Package quality is similar to every open-source project, which means it is hit or miss. I found that Rust has fewer options and sometimes it is hard to understand which package is the right one. For example, managing thread/async is a whole different story that seem to converge with more mature language into more defined patterns.

Tooling

Github has actions for everything that you want.

Rust has a confusing benchmark library because the most popular one is not the native solution. However, it works well, but I couldn't make it work with my GitHub pipeline as I do with my TypeScript project, which automatically deploys results into a webpage. I could run them but not export the result with the current available Github action on the marketplace.

Rust has a tool called "Clippy" that you can invoke using cargo clippy. It gives a lot of insight into full optimizations.

Finally, Rust works well with VsCode but is not as smooth as TypeScript. For example, you need to save the file from getting feedback (error or warning). Otherwise, VsCode does not "compute" that something has changed. Otherwise, auto-complete and fetching comment for a rich experience is as expected.

Error Message and Warning

First-class level for messages. It clearly identifies the problem and suggests fixes (most of the time). Here is an example of a warning:

warning: you seem to be trying to use `match` for destructuring a single pattern. Consider using `if let`

--> src/main.rs:25:37

|

25 | Ok(steganography_option) => match steganography(steganography_option) {

| _____________________________________^

26 | | Some(s) => {

27 | | print!("{}", s);

28 | | }

29 | | None => { /*Nothing to print. Happen if encrypt or if an error occured*/ }

30 | | },

| |_________^

That is quite clear compared to a stack in JavaScript (or Java/C#) without any suggestion.

Complexity

So far, Rust has a steep learning curve. That is well known! But, it is only when you touch Rust that you realize. I've been doing software development for many years with VB, PHP, Java, C#, JavaScript and TypeScript with all over three years each. I already had some academic knowledge of Python and C++. With all that background, I still find Rust to be a challenging walk. For example, basic stuff like concatenating string can be written in several ways and are all verbose. The scope ownership, borrowing, and dereferencing add a layer of thinking that distance you from your goal of making features. However, Rust is a low-level programming language, and that is the price to pay to be almost barebone to the computer instruction without touching assembly. The price is great performance and safe code.

Safety

Rust has the reputation of being type-safe. However, I found that if you have two unsigned (only positive numbers) that you subtract which could lead to a negative (signed number) will fail at execution time. Maybe the type safety is only for null reference exceptions (pointer of memory), but I found it surprising to fall into that problem rapidly.

Type

Type in Rust is significant. While Rust can infer, you need to think twice about type that you do not in TypeScript/JavaScript. For example, a number needs to be defined, whether it is signed, and what size. A question that you do not need to think about. Similarly, using str or String (and then you will read string slice) is a question in Rust. It is correct, but coming from other languages can add more delay to producing something since you need to think twice to some details that you do not have in some other situations. Also, each type can be mut or not. It is a new paradigm that takes some time to get use to.

Learning Rust

The Rust documentation is a good start. I was pleased to start my journey with well-defined documentation. However, midway I noticed that the detail needed to be shorter and shorter, with more links toward incomplete or non-existent content. It looks like it started strong and was mostly abandoned. There are still many resources online, but a fraction of what you can find with TypeScript/JavaScript.

Conclusion

I am still interested and will continue my journey of learning Rust on the side. I'm on Rust slowly as I am not actively professionally working with Rust. Rust is in a peculiar situation where Java monopolizes a considerable part of the market for backend applications with C# for a company that is more Microsoft-centric and C++ for the high-performance situation. Where go Rust remains a good question. I see potential when you want to avoid installing a heavy virtual machine that Java requires while remaining cross-platform. Rust is also a good replacement for C++ as it helps avoid memory issues. However, as of 2023, many high-performance jobs already have a set of skilled C++ developers and for more business-oriented backend have strong Java developers who like popular frameworks like Spring. The steep learning curves do not have the advantage of developing Node backend (using TypeScript/JavaScript), which also happens to have the benefit of sharing code between the front-end and backend. Thus, Rust remains interesting, but its place is undefined from my perspective.